While I do have the Vance integral edition, which he doesn’t, I still don’t have a lot of the stuff shown here. Vance collectors are so fanatical that they make my bibliomania look relatively sane by comparison…

(Hat Tip: Mike Berro)

While I do have the Vance integral edition, which he doesn’t, I still don’t have a lot of the stuff shown here. Vance collectors are so fanatical that they make my bibliomania look relatively sane by comparison…

(Hat Tip: Mike Berro)

I can’t believe I linked this before Dwight. Sadly, it appears to be a parody.

Then again, I suspect that a board-game version of The Wire might sell really well. Hell, for all I know, it already exists…

You may have heard about science fiction fanzine Space Squid printing one of their issues on the ultimate form of Dead Media: inscribed in cuneiform on a baked clay tablet. Of these, I think they auctioned off five at Armadillocon.

Being one of the few people in the world with a complete collection of Space Squid issues (they actually told me that Nova Express was one of their sources of inspiration, the poor deluded fools), naturally I had to pick one up, which I did for the munificent sum of $11. (Bidding seemed more brisk for the usual cats-with-wings and dragon-related art items.)

My tablet. Let me show it to you.

Click to gallery-ize, the click again to embiggen. The first picture is of it sitting in its resting place on my mantelpiece, and the other two pics are close-ups of the front and back. (And here’s another Wired story with pics.)

In truth, the tablet (which contains the Kevin Brown story “Hunting Bigfoot”) is actually pretty hard to read, and I’m not sure how permanent the medium is; the clay has a tendency to flake off. Still, I’m sure that some 50 years hence an insane fanzine collector will be paying big bucks for one…

Here’s Matthew Bey’s step by step tutorial on how he created them.

The Collected Stories of Phillip K. Dick, Volume 2: Second Variety

Underwood/Miller, 1987

People think I’ve read every damn SF book in the world, but this isn’t even remotely true. For example, I’m still trying to catch up to the works the previous generation of SF readers read when they were growing up. So while I’ve generally read the highlights of their work, I’m still trying to catch up on authors like Henry Kuttner, C, L. Moore, R. A. Lafferty, Fritz Leiber, Jack Vance and Philip K. Dick.

In this second volume of Dick’s collected short stories, the themes of “what is reality” and “who is human” that would dominate so many of his novels crops up again and again. The title novella (the longest here) is set during a third world war after a U.S./Soviet nuclear exchange, where U.S. forces are only able to hold off the Soviets thanks to the development of semi autonomous “claw” robots assembled in automated underground factories. A U.S. soldier goes out under truce to a small band of Soviet survivors, only to have a little boy tag along behind him, a boy that’s shot on sight approaching the bunker, as he’s one of two known “impostor” claws varieties in human form. In the bunker, our protagonist is told that there’s a “second variety” of impostor, who’s form is unknown. Paranoia ensues, especially when he returns to his own bunker to find out they’ve been overrun by claw impostors. “Human Is” and “Impostor” also question what it means to be human, and how can you tell if you’re really human?

“Adjustment Team” is another Dick story where the protagonist finds out that Reality Is Not What he Thought it Was, being given an accidental glimpse of something adjusting the world. Believe it or not, they’re making it into a romantic comedy starring Matt Damon and Emily Blunt. Because “romantic comedy” is the first thing you think of when talking about the work of Philip K. Dick. (Although “The World She Wanted,” in which absolutely everything goes exactly right for the woman the protagonist meets (because, after all, it is her world) could also be considered one.)

By this point, Dick was already a technically proficient author capable of moving a story swiftly along with a minimum of wordage. The overwhelming majority of stories in this volume come in at 10-20 pages long, and finish long before they wear out their welcome. As with all Dick’s work, none is perfect, but all have their points of interest. Amazingly, every story in this book (according to the notes at the end) was turned out between August 27, 1952 and April 20, 1953, a rate of productivity that was probably only surpassed by Robert Silverberg at the highpoint of his robotic pulpy period. I can only imagine what sort of effect these stories had on the field when they were originally published, and they’re still well worth reading today.

Lovely acoustic version of Devo’s “Jocko Homo”:

This might be a good time to alert you to the new Devo album that came out earlier this year, Something for Everybody, which I quite enjoyed. It sounds like Devo is trying very hard to recapture their classic sound. For other bands this would be cheesy, but given their devolutionary shtick, for them it works perfectly.

I would also provide an iTunes link for that, except Apple’s LinkShare partner is evidently too stupid to work with Firefox…

This entry, here. Evidently publishing some dozen-odd books doesn’t make you “notable” enough.

The deletion discussion page is here.

At this point I would rant about the deletion of my own entry from Wikipedia a year ago by some wrestling fan who objected to the review Howard Waldrop and I did of the Watchmen movie, but that would mean actually caring what the usual Wikipedia idiot zealots think. It’s simply wiser and easier to ignore them entirely.

I can’t believe I missed this Jess Nevins piece over on No Fear of the Future talking about 19th century SF writer and astronomer Camille Flammarion (I have a couple of first English-language translations of his work) scheme to avert war by having all the armies of Europe dig a giant hole in the ground. This probably wasn’t the wackiest naive pacifist scheme to avert war in the 19th century (though it is even wackier than, say, teaching everyone to speak Esperanto; see Howard Waldrop’s story “Ninieslando” for more details on how that worked out…)

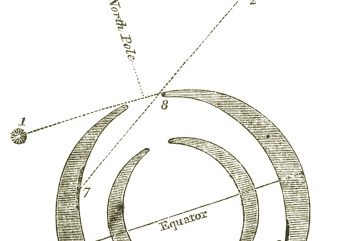

But I’m also fascinated by the Hollow Earth theories propounded by John Cleves Symmes, Jr., who in 1818 proclaimed:

I declare the earth is hollow and habitable within; containing a number of solid concentric spheres, one within the other, and that it is open at the poles 12 or 16 degrees; I pledge my life in support of this truth, and am ready to explore the hollow, if the world will support and aid me in the undertaking.

As wacky cosmological theories, this one had a lot going for it (and certainly more than, say, the theories of Immanuel Velikovsky). For one thing, given the state of exploration and geology extent in 1818, it wasn’t clearly wrong. For another, the idea of internal worlds, of delving deep into the earth, has always fascinated mankind, from the Greek and Sumerian underworlds all the way up through The Mines of Moria, Dungeons and Dragons, and even Minecraft. (Not to mention those Denver airport and Dulce base conspiracy theories.)

Symmes theories even inspired a novel. (Note: The person who put up that e-text of Symzonia says even reprints are rare, but this is no longer the case, as Amazon and Bookfinder are lousy with POD editions.) And Edgar Allen Poe would use some of Symmes’ ideas in The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym.

Another permutation of the Hollow Earth idea was Richard Shaver’s Shaver Mystery. Shaver claimed to hear voices in his head while using welding equipment, and claimed that “detrimental robots” (or deros) lived inside the earth and beamed mind control rays at the surface dwellers. For a while Amazing publisher Ray Palmer had every crackpot in America writing letters to add to the mystery in the late 1940s, just when when the first wave of flying saucer mania was reaching its peak.

Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Pellucidar series is set in the Hollow Earth, and an ever-growing number of science fiction writers have taken advantage of the idea, from Howard Waldrop and Steve Utley’s “Black as the Pit, from Pole to Pole” to Rudy Rucker’s The Hollow Earth, which also features Poe.

Believe it or not, there are some who still believe in the Hollow Earth theory. (Of course, there are still people who believe in a flat earth as well. And they’re looking for new believers once again!)

For more information, I would suggest looking up Walter Kafton-Minkel’s Subterranean Worlds, but since Loompanics Press went out of business (the people currently using their website just picked up the domain name when it lapsed), it’s gotten a bit pricey. I have David Standish’s Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizations, and Marvelous Machines Below the Earth’s Surface, but I haven’t read it yet.

Over on No fear of the Future, Matthew Bey takes a break from Space Squid and Zombie Lapdance-related activities to take a behind the scenes tour of the Texas A&M Cushing Library Science Fiction and Fantasy Research Collection. I donated some Nova Express proofs to them back when Hal Hall was running the library, but he retired about a month back and handed the reins over to Catherine Coker. Someday I’d like to have the chance to look through a science fiction library even bigger than my own. If you have any SF books, magazines, fanzines, etc. you’d like to donate, I’m sure they’d love to hear from you.

And as for that Space Squid clay tablet, I hope to have more information up here about it Real Soon Now…

From Blur Studio.

The Texans beat the Oakland Raiders 31-24. I didn’t watch the entire game, so here are a few random observations: